C# Closures: Mostly harmless

Take a look at the following code snippet:

public class MyButton : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] Button button;

void Awake()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

{

button.onClick.AddListener(() => Debug.Log(i));

}

}

}

It’s a bit weird, but mostly harmless, right? Think about it a little, what’s it going to print when the button is clicked?

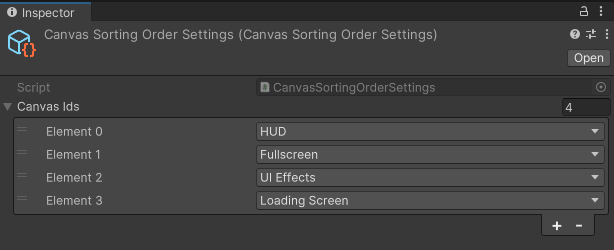

Here's the answer:

It prints "5" 5 times.

Now let’s try this one:

public class MyButton : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] Button button;

void Awake()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

{

int index = i;

button.onClick.AddListener(() => Debug.Log(index));

}

}

}

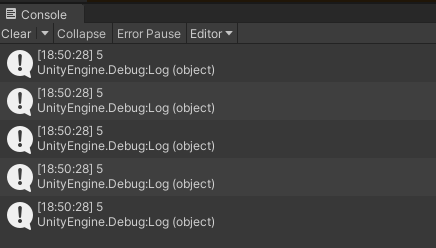

Now it prints “0”, “1”, “2”, “3” and “4”.

Why is that?

The answer is closures. Let’s see how it works in detail.

Definition

You can find the full definition in the Wiki page, but it’s one of those “monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors” definitions, so let’s try something else. To keep things simple, let’s call it a closure when a function stores and references variables that are out of its scope. Now that we are aware of this, let’s rewrite the first example without using lambdas.

Handmade code

public class MyButton : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] Button button;

void Awake()

{

MyFunctionWrapper fnWrapper = new();

while (fnWrapper.i < 5)

{

button.onClick.AddListener(fnWrapper.Invoke);

fnWrapper.i++;

}

}

class MyFunctionWrapper

{

public int i;

public void Invoke()

{

Debug.Log(i);

}

}

}

This is the equivalent of our first example, the one that prints “5”, without using lambdas. Now it’s pretty trivial to understand what’s happening.

We created our own wrapper that holds the i variable instead of declaring it in the Awake scope, and we are sharing the same instance of fnWrapper for all calls of button.onClick.AddListener, hence, they’ll be always referring to the current value of i, which is “5”.

To simulate our second example, the one that prints from “0” to “4”, we need to change our Awake method a bit:

void Awake()

{

int i = 0;

while (i < 5)

{

MyFunctionWrapper fnWrapper = new();

fnWrapper.i = i;

button.onClick.AddListener(fnWrapper.Invoke);

i++;

}

}

Pretty simple, right?

Temporary allocations and garbage collection

Now, some of you might have noticed that we are creating quite a few objects here. In this case it’s not really an issue because those listeners are probably going to stay around for a while, but let’s check this code below:

public class Foo

{

public int Id;

}

Foo FindById(List<Foo> myList, int id)

{

return myList.FirstOrDefault(x => x.Id == id);

}

If we switch this lambda for our manually implemented MyFunctionWrapper, it’ll create a new instance of MyFunctionWrapper every time FindById is called.

This can be a real annoyance for our friend Garbage Collector, moreso if this function is frequently called, like in an Update.

But what about the official implementation? How does the compiler actually resolves a closure?

Compiler output

I’ve simplified the code a bit so we can focus on the closure. Let’s see the compiler output.

Original code:

public class MyButton

{

void Awake()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

{

var fn = () => Console.WriteLine(i);

fn();

}

}

}

Compiler output:

public class MyButton

{

[CompilerGenerated]

private sealed class <>c__DisplayClass0_0

{

public int i;

internal void <Awake>b__0()

{

Console.WriteLine(i);

}

}

private void Awake()

{

<>c__DisplayClass0_0 <>c__DisplayClass0_ = new <>c__DisplayClass0_0();

<>c__DisplayClass0_.i = 0;

while (<>c__DisplayClass0_.i < 5)

{

Action action = new Action(<>c__DisplayClass0_.<Awake>b__0);

action();

<>c__DisplayClass0_.i++;

}

}

}

As you can see, the implementation is pretty similar to what we did above, except some weird names. Give the second example a try with SharpLab and you’ll see that it’s also similar.

So, yes, it’s just as bad for the Garbage Collector. In this case, if you’re dealing with a performance sensitive context, it might be good to avoid closures. If it’s unavoidable, you can try rolling out your own function wrapper as we did before and reuse it as best as possible. This is just one of many tricks to avoid GC, I’ll explore some others in a future article.

To finish things up: closures are pretty simple, but they hide sometimes relevant details. Being aware of their inner workings is important for creating performant and bug-free code.